Why last week marks a turning point

for Australian monetary policy

Share the News

It was not long ago that I thought interest rates had a few more cuts coming our way in 2026. Just like a chameleon, how quickly things can change.

Last week could very well mark a turning point for how we think about monetary policy in Australia. The mounting evidence points to inflation running well above target — driven by rising domestic demand — and that calls for higher interest rates, perhaps sooner rather than later.

For months now, economic data have painted a picture of a recovery taking hold. Weakness, where it exists, has shown up only in lagging indicators — and those have not been decisively weak. What we’re seeing instead is a broad-based rebound: consumer spending, which had been tentative, picked up markedly over winter. Business activity has surged since the May election. Every key gauge of sentiment and confidence — across households and industry — is pointing upward.

The housing sector enjoyed a strong spring, with transaction volumes rising and prices firming. It’s notable that investors are taking up nearly half of new mortgages — a share we haven’t observed in a decade. Meanwhile, despite unsettled global conditions, our export prices remain resilient. And the federal budget is outperforming forecasts — yet another signal of underlying economic strength.

Typically, as an economy recovers, the next phase is a rise in business investment. With confidence restored, business leaders often begin committing capital — not just to expand operations, but to boost productivity. The recent strong capital-expenditure data only underscores this pattern.

Each economic cycle looks different in detail — but the broad mechanics remain: rising demand fuels incomes; incomes drive consumption; consumption supports investment; and the cycle continues. In a world without central banking, the market price of money would simply rise in tandem with these dynamics.

But with a central bank in place, the job of monetary policymakers is to respond — to ensure that monetary conditions do not lag economic momentum. Falling behind risks an overheating economy. And if policymakers have to play catch-up later, restoring price stability could require sudden, sharp interest rate rises — a “hard landing.”

Avoiding another steep rate shock — like those experienced in 2022 and 2023 — should now be a priority for the RBA. Until now, the RBA’s tightening cycle has been dictated by conservative caution, followed by hopes for easing.

The inflation numbers from the September quarter were startling: headline inflation surged at a 5.5 per cent annualised pace, and core inflation at about 4 per cent. According to the RBA, some of that was driven by temporary influences. But when they revised their forecasts a month ago, the medium-term outlook barely changed. The message seems to be: adjust, but don’t pivot.

Then came the first release of monthly CPI data last week — covering October — and once again, prices posted broad-based gains. That result makes it increasingly unlikely that this is a short-lived spike.

Underlying inflation — already in its fifth straight year above the mid-point of the target band — now appears to be rising away from the target, not towards it. The implication is stark: Australia no longer has price stability.

Combine that with the clear signs of a cyclical upswing and the implications for monetary policy become profound. The current overnight cash rate is too low. After three rate cuts this year, monetary policy is anything but tight — if anything, it is loose.

With the RBA’s next board meeting weeks away, the room to wait is shrinking. Prolonging inaction only raises the odds of needing a future cash rate of 6 per cent at some point in the next two years — the so-called “disaster scenario.”

What should the RBA do?

In my view, the logical step is a minimum 25 basis point cash rate increase at the next meeting. This of course will not solve the inflation problem, but it might just help prevent Australian’s paying very high mortgage rates, because the RBA did not act quickly enough. A couple of small increases is certainly better than delaying it, then increasing by ten rate rises because they were too slow.

Markets ought to prepare for further tightening in 2026. A 4.35 per cent cash rate — after more than 400 bps of tightening already — failed to deliver price stability. There’s little reason to believe a lower cash rate can do any better now.

Delaying further only deepens the risk that restoring inflation to target will require a far more painful adjustment later. That’s not just risky for the economy — it’s risky for the people, and it’s risky for the credibility of the RBA.

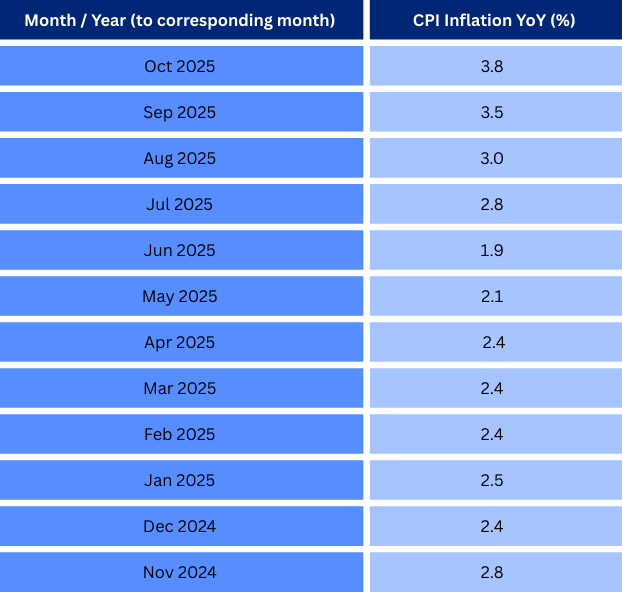

Recent 12-Month Inflation (Monthly CPI Indicator) — Australia

(Annualised change; latest available month: Oct 2025)

Note: The data reflect the annualised percentage change for each month, as measured by the monthly CPI indicator — the timely inflation metric recently adopted as Australia’s primary inflation gauge. Reserve Bank of Australia+2Reserve Bank of Australia+2

I certainly do not profess to be a political expert, but the unemployment rate is incredibly low, primarily due to government hiring. Once you take these jobs out of the market, unemployment figures are a lot higher. So, with the Treasurer complaining about inflation, perhaps he should influence the government to stop hiring so much. It is artificially creating this inflation headache we can’t seem to get rid. Just my 2 cents.

What this all means — and what to watch

→ The most recent print (October 2025: +3.8 per cent) represents a clear acceleration after a period of deceleration through mid-2025. That suggests inflationary pressure remains more persistent than transitory.

→ Given the economic backdrop — rising demand, improving consumer/business sentiment, strong housing activity, robust business capex — there is a compelling case for tighter monetary policy.

→ The longer the policy stays loose, the greater the risk that inflation becomes entrenched — making it more painful (and potentially abrupt) to rein it in later.

→ For borrowers, businesses contemplating investment, and households budgeting for the future, these dynamics warrant serious consideration: a higher cash rate over the coming 12–24 months is becoming an increasingly likely base case.